Met with seasoned copper gravure printmaker Barbara Sanders this week and had a lively exchange of information with her and her ceramicist husband Bill regarding the craft and business side of art. Barbara is migrating from copper to polymer with great success as she works toward “close enough to perfect” to feel good about the process. This is the quandary with most printmakers as our thirst for perfection is hard to quench.

The main geek topic of our conversation was how to best start to derive a compensation curve and exposure times. Barbara had taken a sample of my company’s custom aquatint screen back home with her after our meeting and came back with some absolute numbers. Here is the email exchange and some of my thoughts about starting to derive a curve, screen exposure time and image exposure time:

—–Original Message—–

From: Bill and Barbara Sanders

Sent: Wednesday, January 16, 2013 9:48 AM

To: Jon Lybrook

Subject: thanksSuch a fun afternoon!

Thank you for taking the time to see me and my work. I sure love your prints!

I measured the density of your screen : about 53/54 whatever units the densitometer is in

my new screen : about 168/170

my old screen : about 80/83

hence the different exposure times aside from our different exposure units wattage. Complicated but still fun!

Off to Mac class!

Many thanks again.

Barb———————————-

Thanks Barbara,

Thanks for the screen measurement. Like I said I don’t know a lot about measuring density. I guess because I pretty much worked out my process backwards from the resulting print back to the curve and exposure times. The absolute density of a screen and film positive meant nothing to me in the beginning since I had no point of reference, unlike photogravurist John Goodman and those who have had a historical knowledge of their materials and the process. I could only hope my screens were consistent, and so far they have seemed to be. But I am curious about it and appreciate your encouragement in that direction. It would help to verify consistency among my limited stock of custom screens.

Since these screens are made up of dots, as black as we can get the imagesetter to produce them, I’m assuming it’s taking an average of the dots-to-clear-film ratio and coming up with a number. In other words, it’s not measuring a continuous-tone density as traditional film provides, but rather a combination of these factors.

I’m presuming your screens read darker because the dots are bigger, allowing less light to come through. Not because the dots on your screens are more opaque than mine, though if your exposure time of the screen/image is too high, the density of the dots on the screen would certainly be a factor as well.

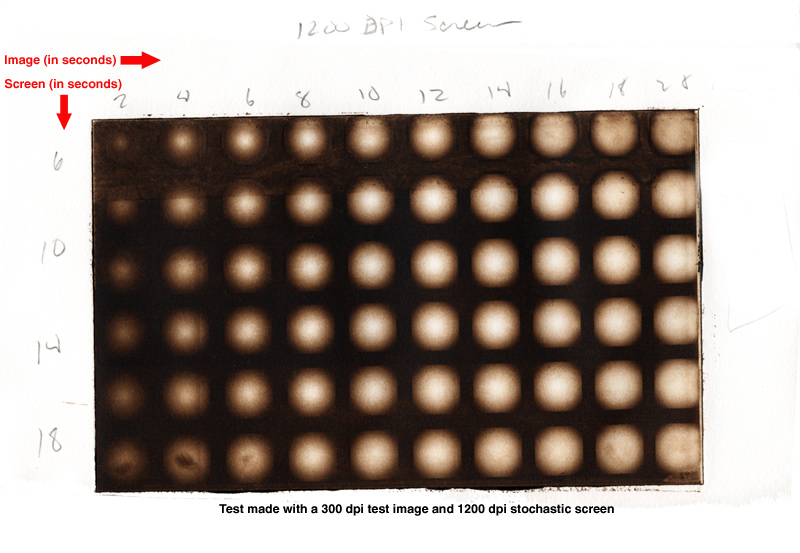

To get a good curve and exposure time relationship, I test first by getting the screen to produce the richest black in my exposure and still provide tone up the scale. This is where

Gradient circle test Grid by Intaglio Editions

those gradient circle tests in my procedure occurred – to get a ball-park sense of where I am. I would then tweak the curve in conjunction with exposure times until I was able to maintain a rich black and get some added continuous tone in the highlights. Trying to keep the black where it was, I’d tweak the process compensation curve and exposure times as needed to bring out more and more of the greys in both shadows and highlights. Kind of like chasing your own tail in a way at first, but these factors start to even out if the testing is paced and consistent.

Subtle, but possibly relevant point pertaining to the quality of the outcome and the reason why I went with an extremely fine screen: Bigger the dots, the more contrast, the more contrast, the less possible grey tones. I like lots of grey-tone potential because you can always add contrast in the film transparency and make it more graphic if you want to, but you can’t add broad continuous tone until you’ve been able to achieve it already through a balanced combination of the process compensation curve along with proper exposure times of the screen and film positive.

Best of luck with your curve training. Let me know if there are any questions I can answer in your journey!

Best regards,

Jon

.