We recently made a major change to our plate making workflow at Intaglio Editions, and added new quality-control steps for monitoring any changes in plate sensitivity among plate batches. We also confirmed changes in plate sensitivity occur in Toyobo KM73 plates over time — even when stored in ideal, light-safe conditions. Thanks for Clay Harmon for bringing this important variable to my attention in his artful book on making Double-Exposure polymer photogravure plates: Polymer Photogravure: A Step by Step Manual Highlighting Artists and their Creative Practices

This change in workflow includes employing a new method of deriving our process compensation adjustments using the Easy Digital Negatives system by Peter Mrhar. His method for deriving adjustments is effective, comprehensive and includes calibration workflows for scanners, spectrophotometer readings, as well as eyeballing it for those interested in doing it the hard way! The ability to calibrate a process compensation adjustment for any colored ink and paper has given us a much greater degree of control, no matter the ink color or medium.

Although his color blocking system looked promising for creating deep, rich blacks, foregoing it worked better for our workflow as it was introducing posterization we couldn’t address.

With such highly calibrated plates, I wanted to verify our assumptions about the go-to papers I’ve used for over a decade, and introduce some newer papers, and those we’ve had trouble with before, including 100% cotton papers, which introduced a white haze in our solid, rich blacks consistently. We’ve generally had much better luck using Hahnemuhle Copperplate papers. Wood fibers in the alpha cellulose seem to provide more solid fields of black with our workflow and custom 1245 dpi aquatint screen.

The Torinoko 92gsm gampi from Japan had the best fidelity of the three gampi papers we tested this round. The solid blacks, shadow detail, and crisp transfer from the plate make up for the fragile surface, which can easily be abraded in handling. The paper has an antique, suede feeling and texture and prints as well as the most expensive gampi papers.

Fine art printmaking papers used in our testing include:

Japan

Germany

UK

France

Italy

* = Waterleaf paper that contains no starch or sizing.

We purchase all of our editioning papers through Takach Paper for their quality service and experience.

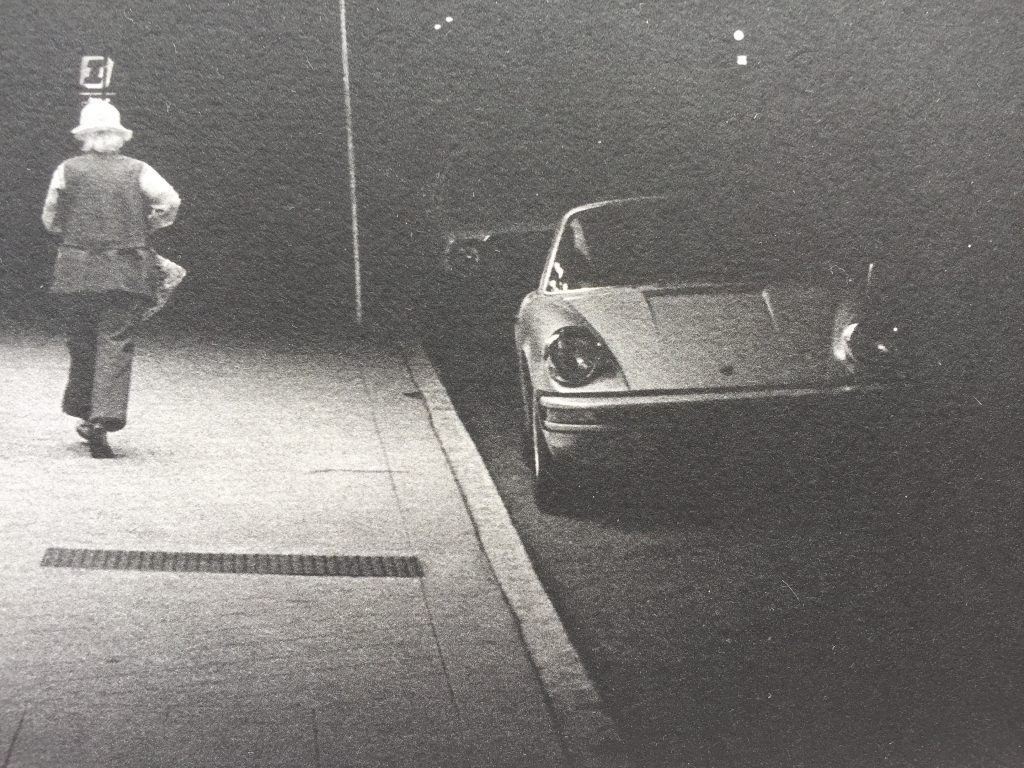

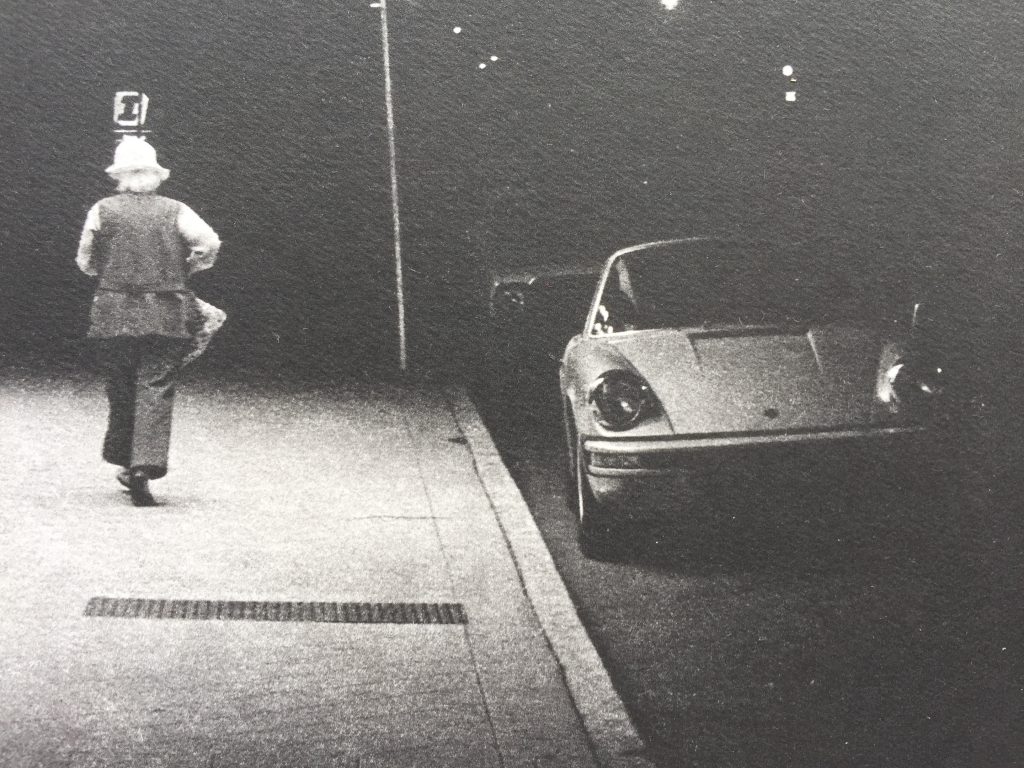

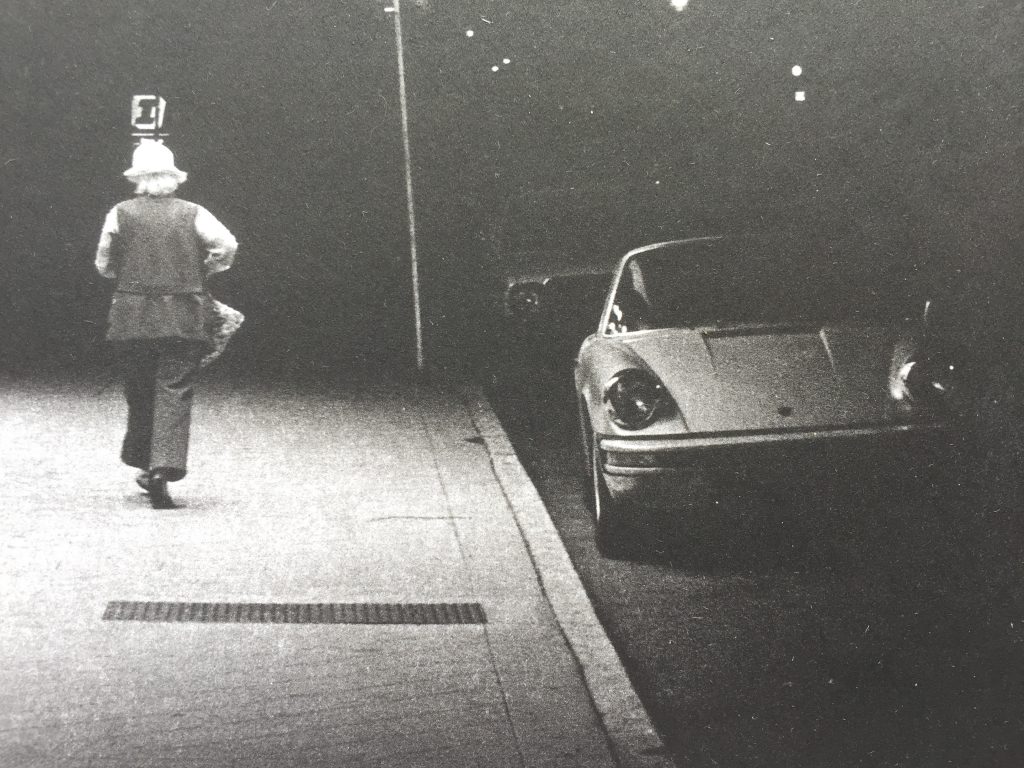

Photos and proofing stills courtesy of the photographer, Tony Levin.

NOTE: We have intentionally photographed the images below under a raking light to best illustrate the benefits and shortcomings of the different papers proofed under identical conditions. All the papers were pre-calendared and had the same approximate drying time. Click to enlarge details on any of the images below.

Consistent in continuous tone and image integrity, Hahnemuhle Copperplate remains our go-to paper for proofing and editioning.

Unlike the Copperplate, this radiant white Cotton Rag paper by Hahnemuhle did not hold up as we had hoped. It tested out as the worst paper for photogravure with our plates. We were consistent in steps for calendaring the paper, as well as printing without to give each paper every opportunity to show its unique qualities.

This classic waterleaf paper is designed for silkscreen and monotype. It’s 100% Cotton fiber makeup and zero sizing did not provide adequate structure to absorb the ink from our plates as cleanly as other papers.

We likewise had high hopes for Incisioni as it was the brightest white paper we tested. Although the contrast and quality of blacks created the most photographic-looking prints, it was too much of a good thing. With work, calendaring and careful assessment of paper moisture before printing we were able to get acceptable results.

======

Conclusion: While 100% Cotton paper can be problematic in getting optimal continuous tone with Intaglio Editions plates, the cotton papers Lanaquarelle and Somerset Velvet printed relatively well, with the clear champions remaining Hahnemuhle Copperplate “Bright” White and Warm White, and the 92gsm Torinoko gampi for the best looking Asian paper for the price for simple, one-drop photogravure prints and editions.